Topics : People of the Margins

Hills and Plains in the Jaintia buranji

The invention of matrilineality among the Jaintia kings: materials from the Deodhai buranji.

Introduction

This series of diagrams pertain to the invention of matrilineality as narrated by the two Jayantā janmakathā of Deodhai Būranjī ed. By S.K. Bhuyan, DHAS, Gauhati, 1962 (pp. 134-140). The editor mentions the origin of these versions, states that they are collations, but does not seem to know their first origin. If the genealogy given in the first janmakathā is to be trusted, the events narrated could have taken place sometime around the second half of the XVIth century.

The translation in English used here is from a work in progress within the Brahmaputra Studies project by the Linguistics Dept, Un. of Gauhati, under the supervision of Prof. J. Tamuli. The Assamese reader may refer to S.K. Bhuyan's publication mentioned above which also contains an English summary (pp.XXX-XXXIV). Additionally, Soumen Sen has provided a free, although detailled translation of Jayantā janmakathā in "For King's Sake...", Indian Folklore Research Journal, 1-1, 2001, pp.1-12. He considers these texts as an entreprise of sanctification of the royal order from an Hindu point of view, intended at the plains subjects of the kingdom (op. cit. p.9). So in Sen's view, Jaintia buranjis would be the plains version of the foundation myth, as opposed to the hills' versions he summarizes in the same article. We widely agree to this point of view, if it does not imply that the buranji would be a "corrupted" or "unauthentic" version of an "original" narrative more representative of the indigenous views. We assume that it is as useful as the hills myths for the understanding of Jaintia culture and representations. Although in the hills, Hinduism (or pan-Indian culture or plains culture...) was prevalent mostly among the elite, its influence has been widespread and ancient. The recent efforts by the revivalist movements to promote the "indigenous" components of the local culture by cleaning it from the external ones may be honourable. Incidentally, they show that Khasi or Jaintia cultures had not developped as sealed isolates. Nevertheless they should not lead us to disregard the symetrical exchanges between lowlands and highlands The documents and analysis pertaining to hills narratives, that we will present on this site in the near future, will show that very similar motives, articulated along similar structural paradigms were shared by communities living in very contrasted ecological zones. Thus it is impossible to easily oppose "Hindu plains" and "Tribal hills". Secondly, as these myths were supposed to be the official ones, it is highly probable that they had a certain influence, not only among the discret circle around the Jaintia sovereigns, but among their general subjects as well. Finally, as suggested by the analysis we present here, the content of Jayantā janmakathā may on the opposite be regarded as a recognition by the plains elite of the hills' contributions.

<- top

Birth and marriage of Jāyantī

The whole story is a very sophisticated as well as a very concise account about the establishment of matrilineal descent and succession rules, through the making of relationships with the hills and with the divine intervention of Goddesses at each stage.

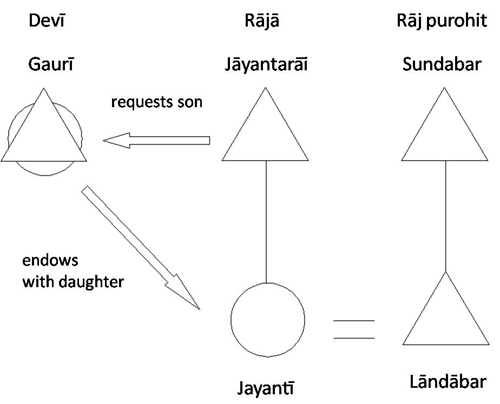

Fig. I.1 The two versions of Jayantā janmakatha are very similar. The first one describes Jayantāpur's royal house as spreading out from a Brahman dynasty with origins in the Mahābhārata. The king Jayantārai remains childless. The Goddess offers him to make a girl born, who will become the heir. The royal princess, Jayantī, is married to Lāndābar, the son of the rāj pūrohit.

Flight to the Hills

Fig. I.2 The outrageous behaviour of Lāndābar towards both his wife and the Goddess makes him expelled from the capital. He is adopted by a couple of Garos as their son. The Garo is named Suttangā (which evokes Sutnga, in the hills, the cradle of the dynasty in other narratives). Lāndābar thus shifts from one world to another, i.e. from the civilized plains to the wild hills (the myth does not speak of hills or plains but we may without too much risk interpret that the Garos is conceived as inhabiting the hills). At this stage, plains and hills, or at least the capital and the land of the "Garos" are still symbolically separated. The second version starts only at this point, with the hero being qualified only as a "Garo bachelor of Nartiang" (note: Nartiang is definitely situated at the core of the hills. Down to XIXth century it was alternatively an autonomous principality and the summer capital of the Jaintias. Its Devi's sanctuary had a major importance for all the communities of Eastern Meghalaya plateau. The mention of "Garos" in this area is a subject of investigation in itself as no major Garo settlement is found there nowadays). The following events are almost similar in both versions. A divine girl, Matsyodari (actually the sister of Jayantī), incarnates in a barāli's fish womb. The fish is captured by the Garo. Matsyodari reveals her divine origin and becomes his mate. She predicts that wealth will come and that the Garo won't need to cut the ara plant anymore.

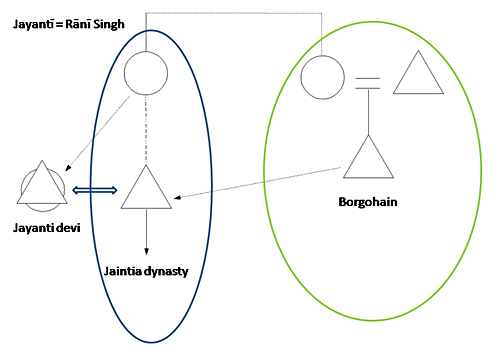

Back to the plains

Fig. I.3 Matsyodari and Landhabar conceive a son, Borgohain, endowed with skills and fortune. Borgohain becomes the head of the group of villages – supposedly Garo – which clashes with the neighbouring Jayantiya kingdom. But Borgohain is called by Jayanti, who reveals he is the son of her own sister. She requests him to become the new king, herself disapearing to be worshiped as a goddess, Jayanti Devi, being in fact the tutelary deity of the dynasty.